In this week’s class, we focus on a single question. We will be using the short booklet ‘The Victory of the Cross’ by St. Dumitru Staniloae as our key resource as we examine this question:

- What do the crosses we experience in our relationships have to teach us

We will also review our results from how we dealt with the cross of technology and distraction this past week. As you might remember from our last class, William suggested this as a somewhat universal cross that all of us must face in this tension we live in of ‘being in the world’ but ‘not of the world’. The Orthodox practice of nepsis or watchfulness comes to mind as something that can be helpful here. OCA Bishop Alexis Trader (Bishop of Alaska) has written a book about ‘Ancient Christian Wisdom’ that I find has a helpful quote about some of the specific tools we can use to promote this watchfulness:

For the ancient ascetics, watchfulness can be likened to Jacob’s ladder extending up into the heavens and to a pathway leading to the kingdom within where the believer encounters a “spiritual world of God, splendid and vast”. The fathers refer to watchfulness as “stillness of heart, attentiveness, guarding the heart.” Saint Hesychius the Presbyter describes four approaches to watchfulness: calling out to Christ for help, remaining silent and still in prayer, remembrance of death (i.e. keeping things in perspective), scrutinizing our thoughts (i.e. honest appraisal of what’s happening).

Ancient Christian Wisdom p. 197

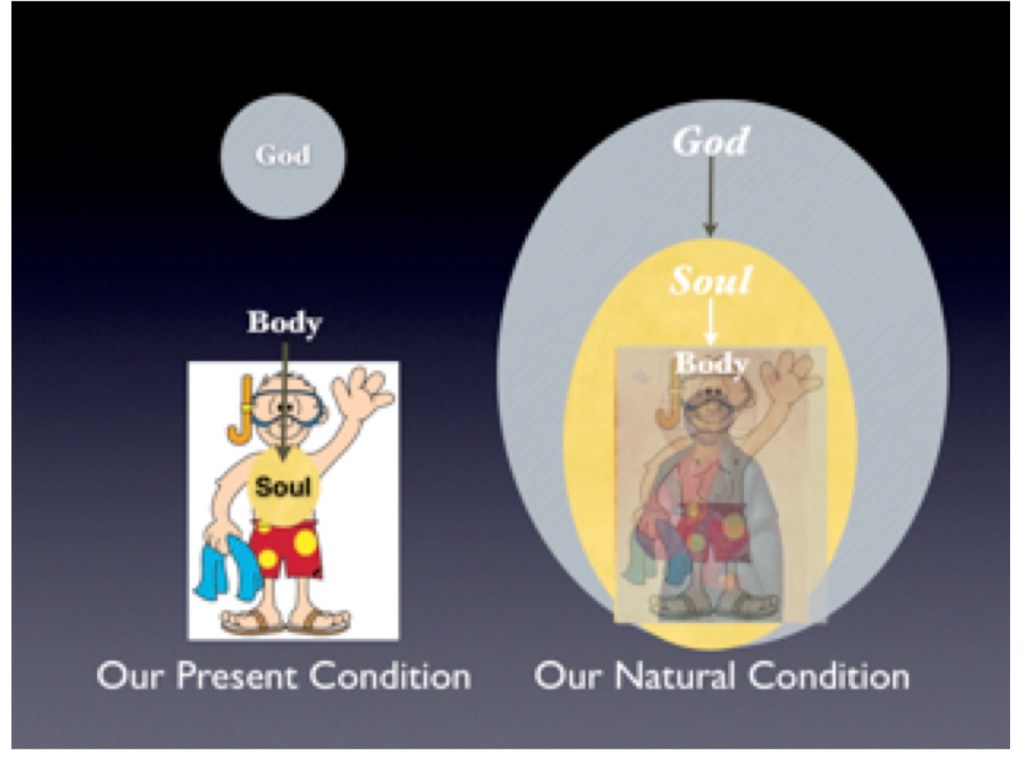

I believe this cartoon we’ve used in previous classes is an appropriate way of thinking about the movement we’re attempting as we face this cross of technology and distraction that seems so deeply woven into each of our lives.

What do the crosses we experience in our relationships have to teach us?

Our responsibility towards those who are near to us forms the weight of a particularly heavy and painful cross on account of the fragility of their life which is exposed to a multitude of ills, a multitude of difficulties which arise from the conditions of this world in its present state. Parents suffer intensely and very frequently because of the ills and difficulties of their children; they fear for their life, for their failure, for their sufferings. Therefore the life of parents becomes a life of continual concern, and the cross of the children is their cross. Our cross becomes heavier with the weight of the cross of those with whom we come in contact, for we share responsibility for the life of our children, our relatives, our friends, and even of all men with whom, in one way and another, we are in touch. We bear responsibility for all that can threaten the life of those for whom we have care, and we have the obligation, so far as we can, of smoothing their difficulties and helping their lives. Thus we can reveal and strengthen our love for them and their love for us; thus we can develop the seeds of a future life in strengthening our and their spiritual existence. In this responsibility towards our neighbour we live more intensely our responsibility towards God. Christ has shown this meaning of his cross, he who had pity on those who were suffering, and wept for those who were dead.

A second sense of the cross in relationships is this: the fallen world is often lived and felt as a cross to be carried until death through the fact that people sometimes act towards us in a hostile way, even though we have done them no wrong. They suspect us of having evil intentions towards them. They think of us as obstacles in the path of their life. Often they become our enemies even on account of the noble and high convictions to which we remain faithful. Our attachment to these convictions brings their evil designs into the light and their bad intentions to view even though we do not intend this. And this happens all the more because by the beliefs which we hold, and which we cannot renounce, we show our responsibility towards them, since we seek the security of their physical and material life and the true development of their spiritual being. This is a responsibility which we reveal in our words, our writings and our actions which become, as it were, an exhortation to them.

We also feel as a heavy cross the erring ways of our children, of our brethren, and of many of our neighbours and contemporaries. We carry their incomprehension of our good intentions and of our good works as a cross. Almost every one of our efforts to spread goodness is accompanied by suffering and by a cross which we carry on account of the incomprehension of others. To wish to avoid this suffering, this cross, would mean in general to renounce the struggle and the effort to do what is good.

Thus without the cross there can be no true growth and no true strengthening of the spiritual life. To avoid the weight of this cross is to avoid our responsibility towards our brethren and our neighbours before God. Only by the cross can we remain in submission to God and in true love towards our neighbours. We cannot purify or develop our own spiritual life nor that of others, nor that of the world in general, by seeking to avoid the cross. Consequently, we do not discover either the depth or the greatness of the potential forces and powers of this world as a gift of God if we try to live without the cross. The way of the cross is the only way which leads us upwards, the only way which carries creation towards the true heights for which it was made. This is the signification which we understand of the cross of Christ.

Victory of the Cross p.3-5