Have you ever thought about the similarities and differences between barns and temples? Usually when we think of barns, we think simply of places to house farm animals or to store crops. We normally do not think of them as having much spiritual significance. The rich man in today’s gospel lesson thought of his barns only in terms of his business, which was so successful that he looked forward simply to relaxing, eating, drinking, and enjoying himself. Unfortunately, he did so to the point of making his possessions an idol. He was rich in things of the world, but poor towards God. He was ultimately a fool, for he based his life on what was temporary and lost his own soul. His barn became a temple only to himself.

We live in a culture that constantly tempts us to follow this man’s bad example. More so than any previous generation, we are bombarded with advertising and other messages telling us that the good life is found in what we can buy. Whether it is cell phones, clothing, cars, houses, entertainment, food, or medicines, the message is the same: Happiness comes from buying the latest new product. During the weeks leading up to Christmas, this message is particularly strong. We do not have to become Scrooges, however. It is one thing to give reasonable gifts to our loved ones in celebration of the Savior’s birth, but it is quite another to turn this holy time of year into an idolatrous orgy of materialism that obscures the very reason for the season.

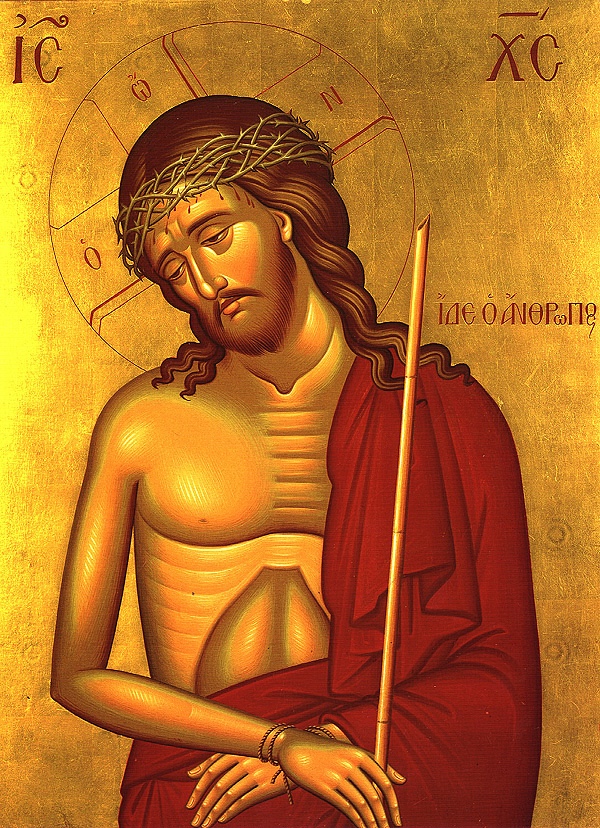

We are not really near Christmas yet, as Advent just began on November 15. Today, as we continue to celebrate the ForeFeast of the Entrance of the Theotokos into the Temple, we are reminded of the importance of preparing to receive Christ at His birth. Instead of looking for fulfillment in barns and the money they produce, we should follow her into the temple. Sts. Joachim and Anna took their young daughter to the temple in Jerusalem, where she grew up in prayer and purity in preparation to become the living temple of God when she consented to the message of the Archangel Gabriel to become the mother of the God-Man Jesus Christ. The Theotokos was not prepared for her uniquely glorious role by a life focused on making as much money as possible, acquiring the most fashionable and expensive products, or simply pleasing herself. No, she became unbelievably rich toward God by focusing on the one thing needful, by a life focused on hearing the word of God and keeping it.

In ways appropriate to our own life circumstances, God calls each of us to do the same thing. And before we start making excuses, we need to recognize that what St. Paul wrote to the Ephesians applies to us also: “[Y]ou are no longer strangers and sojourners, but…fellow citizens with the saints and members of the household of God, built upon the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Christ Jesus Himself being the cornerstone, in Whom the whole structure is joined together and grows into a holy temple in the Lord; in Whom you also are built into it for a dwelling place of God in the Spirit.” In other words, to be a Christian is to be a temple, for the Holy Spirit dwells in us both personally and collectively. The only way to become a better temple is to follow the example of the Theotokos in deliberate, intentional practices that make us rich toward God, that open ourselves to the healing and transformation of our souls that Christ has brought to the world. We must participate personally in His holiness if we want to welcome Him anew into our lives at Christmas.

The rich fool became wealthy by investing himself entirely in his business to the neglect of everything else. In contrast, the Theotokos invested herself so fully in the Lord that she was able to fulfill the most exalted, blessed, and difficult calling of all time as the Virgin Mother of the Savior. In order for us to follow her example by becoming better temples of Christ, we also have to invest ourselves in holiness. The hard truth is that holiness does not happen by accident, especially in a culture that worships at the altar of pleasure, power, and possessions. So much in our world shapes us every day a bit more like the rich fool in our gospel lesson, regardless of how much or how little money we have. Many of us are addicted to electronic screens on phones, computers, and televisions. What we see and hear through virtually all forms of entertainment encourages us to think and act as though our horizons extend no further than a barn. In other words, the measure of our lives becomes what we possess, what we can buy, and whatever pleasure or distraction we can find on our own terms with food, drink, sex, or anything else. We think of ourselves as isolated individuals free to seek happiness however it suits us. No wonder that there is so much divorce, abortion, sexual immorality, and disregard for the poor, sick, and aged in our society. Investing our lives in these ways is a form of idolatry, of offering ourselves to false gods that can neither save nor satisfy us. The barn of the rich fool was also a temple, a pagan temple in which he basically worshiped himself. If we are not careful, we will become just like him by laying up treasures for ourselves according to the dominant standards of our culture and shut ourselves out of the new life that Christ has brought to the world.

We cannot control the larger trends of our society, but we can control what we do each day. During this Nativity Fast, no matter the circumstances of our lives, we can all take steps to live more faithfully as members of God’s household, built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, with Jesus Christ as the cornerstone. In other words, we can intentionally reject corrupting influences and live in ways that serve our calling to become better living temples of the Lord. Yes, we can stop obsessing about our barns and enter into the temple of the one true God.

The first step is to set aside time for prayer. If we do not pray every day, we should not be surprised that it is hard to pray in Church or that we find only frustration in trying to resist temptation or to know God’s peace in our lives. We also need to read the Bible. If we fill our minds with everything but the Holy Scriptures and the lives of the Saints, we should not be surprised that worry, fear, and unholy thoughts dominate us. Fasting is also crucial. If we do not fast or otherwise practice self-denial, we should not be surprised when self-centered desires for pleasure routinely get the better of us and make us their slaves. We should also share with the poor. If we do not give generously of our time and resources to others in need, we should not be surprised when selfishness alienates us from God, our neighbors, and even our loved ones. This is also a time for humble confession and repentance. If we refuse to acknowledge and turn from our sins, we should not be surprised when we are overcome by guilt and fall into despair about leading a faithful life. No, the Theotokos did not wander into the temple by accident and we will not follow her into a life of holiness unless we intentionally reorient ourselves toward Him.

None of us will do that perfectly, but we must all take the steps we are capable of taking in order to turn our barns into temples. Remember that the infant Christ was born in a barn, which by virtue of His presence became a temple. The same will be true of our distracted, broken lives when—with the fear of God and faith and love—we open ourselves to the One Who comes to save us at Christmas. The Theotokos prepared to receive the Savior by attending to the one thing needful, to hearing and keeping His word. In the world as we know it, that takes deliberate effort, but it remains the only way to be rich toward God. And that is why Christ is born at Christmas, to bring us into His blessed, holy, and divine life which is more marvelous than anything we can possibly imagine. As the Lord said, “He who has ears to hear, let him hear.”