By Father Panagiotes Carras

The oikonomia of our salvation began with the very creation of the world. It is not by chance that the fourth Gospel does not commence with a genealogy of our Lord but takes us back to the very beginning. All things from the beginning to the end, from the alpha to the omega are part of God’soikonomia for our salvation, God’s providential ordering of our salvation. Man was created that he may participate in the Divinity of his Creator by first participating in his own perfection. We are taught by the Fathers that man was created for perfection. Adam was offered perfection but fell victim to the guile of the serpent. God’s plan could not be frustrated and the Lord prepared the world for another Adam who would rescue the offspring of the first Adam.

St. Paul tells us that Adam is a type of the future Adam (Romans 5: 14). All Christians are descendants of both the first Adam and the last Adam. From the first we inherited death, from the last we inherited life. (1 Corinthians 15: 45-50). It is this Apostolic teaching of the two Adams which was developed by the Fathers and formed the nucleus of the Church’s teaching on the salvation of mankind.

Mankind, which had its beginning in the first Adam, had to be given a new beginning. A new Adam was needed to become the Head of the New Humanity, the Head of the body, the Church, which is His body (Ephesians 1:22-23). However, just as in the creation of the Old Humanity, mankind was given the freedom to choose sonship; similarly in the creation of the New Humanity, mankind was granted the opportunity to choose. The first Adam was from the earth, a man of dust, the second is from Heaven (1 Corinthians 15: 47). The first could choose sin because he was not yet perfect, the second Adam, our Lord Jesus Christ, being God by nature, was totally alien to sin. It is because God’s oikonomia required a member of the human race who was able to prove himself free from every sin that the time had fully come (Galatians 4:4) for God to send forth His Son, since mankind was able to bring forth the All-Holy Virgin.

This is precisely why Theotokos is the key-word of the Christological teaching of the fourth Ecumenical Council or as St. John of Damascus says, This name contains the whole mystery of the Oikonomia(On the Orthodox Faith, 3, 12). It is for this reason that the traditional Orthodox icon of the Mother of God is an icon of the Incarnation, the Virgin is always with the Child.

The Church’s teaching of the Theotokos is an extension of what is believed concerning the person of Christ. The Son of God was born of a woman and in this case the Mother is not just a mere physical instrument but an active participant who has found favour with God (Luke 1, 30). The faith of the Church is aptly expressed in the words of Nicholas Cabasilas in his Homily on the Annunciation: The incarnation was not only the work of the Father and of His Power and His Spirit, it was also the work of the will and the faith of the Virgin (On the Annunciation, 4).

It is the teaching of the Church, attested to from the earliest date, that the Virgin Mother of the Incarnate Lord had found favour with God (Luke 1:30) and that she was chosen and ordained to participate in the Mystery of the Incarnation, in the Oikonomia of Salvation. The ancient Church understood the typological relationship between the first Adam and the last Adam, and by extension it was able to see that the first Eve prefigured the second Eve. We find that as early as the Second Century St. Justin and St. Irenaeus had a developed teaching of the Theotokos as the second Eve who through her obedience remedied the disobedience of the first Eve. And so the knot of Eve’s disobedience received its unloosing through the obedience of Mary; for what Eve, a virgin, bound by unbelief, that, Mary, a Virgin, unloosed by faith (Against Heresies, III, 22, 4.) Mary… by yielding obedience, became the cause of salvation, both to herself and the whole human race. (Against Heresies, III, 22, 4). Mary alone cooperating with the economy (Against Heresies, III, 21, 7).

The Church has proclaimed this great Mystery of our salvation not only through the teaching of the Fathers but also through the festal celebration of the acts which worked our salvation, chief of which is the Holy Resurrection of our Lord. On the 21st of November the Church celebrates the Feast of the Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple. It is at this time that the faithful chant Today is the prelude of God’s Good-Will and the heralding of the salvation of mankind. (Dismissal Hymn).

Throughout the whole service the hymns proclaim the exalted place which the Entry has in the history of Salvation. The Entry marks the closing of the Old Covenant, whereas the Annunciation marks the beginning of the New. With the Entry the most Holy Virgin is passing from the Old Covenant to the New, and this transition in the person of the Mother of God shows us how the New Covenant is the fulfillment of the Old.

Like other human beings the Holy Virgin was born under the law of original sin but the sinful heritage of the fall had no mastery over her. She was without sin under the universal sovereignty of sin, pure from every seduction and yet part of a humanity enslaved by the devil. This is the victory which the Feast of the Entry joyfully celebrates. St. Photius praises the Holy Virgin as the great and God-carved ornament of human kind” who ” made her whole soul a holy shrine of meekness… never allowing any of her wares as much as to touch for a moment the brine of evil. (On the Annunciation, 4). This theme constantly appears in the hymns of the Feast of the Entry. Thy Miracle, 0 Pure Theotokos, transcends the power of words; for I comprehend that thine is a body transcending description, not receptive to the flow of sin. (Third Magnification of the ninth Ode). Nicholas Cabasilas expanded this teaching and dealt with it extensively in his Homily on the Birth of the Theotokos where we read: The Virgin remained from the beginning to the end free from every evil because of her vigilant attention, firm will, and magnitude of wisdom. (Chapter 15).

The sinlessness and purity of the Theotokos along with the fact that the Lord was preparing Her to become His chamber overshadowed the sanctity of the Old Testament temple. The All-Pure Virgin is allowed to enter the Holy of Holies precisely because she is to become the living temple of God. St. Tarasios in his Homily of the Entry has Saint Anne exclaiming:Receive Zacharias, the pure tabernacle; receive 0 priest, the immaculate chamber of the Word … have her dwell in the temple made by hands, she who has become a living temple of the Word (Migne, 98:1489). Zacharias in turn speaks to the Virgin, You are the loosing of the curse of Adam, you are the payment of the debt of Eveand he continues to recall all the types and prophecies of the Old Testament which refer to the Theotokos. (Migne, 98:1492-93).

In the Minea of St. Dimitry of Rostov we read, Thus with the honor and glory not only of men, but also of angels, the most Immaculate Maiden was led into the temple of the Lord. And it was meet: for if the ark of the Old Testament, bearing manna in itself, which served only as a prototype of the Most Holy Virgin, was carried into the temple with great honor, with the assembling of all Israel, then with how much greater honor, with the assembling of angels and men, had to take place the entry into the temple of that same living ark, which had manna — Christ — in it, the Most Blessed Virgin, fore-ordained to be the Mother of God.

The Feast of the Entry celebrates the sanctity of the All-Holy Virgin and glorifies the Lord who placed her in the inaccessible Holies like some treasure of God’s, to be used in due time (even as came to pass) for the enrichment of, and as an ornament transcending, as well as common to, all the world.(St. Gregory Palamas, Homily on the Entry, IX).

Teachings From the Service of the Feast

In the Orthodox Church services we participate in the saving events of the Oikonomia of Salvation. This is why, during these services we hear the word Today quite often. This is why in the first Sticheron of the Lord I have Cried begins, Come let us faithful dance for joy on this day. The second Sticheron begins with In the temple of the Law today is the living temple. During Vespers, Matins and the Divine Liturgy we enter into the Mystery of the Entry of the Theotokos. When we enter into the Mystery we are not simple witnesses as the maidens who accompanied theTheotokos but rather participants in the eternal mystery.

The first two Old Testament readings of Vespers speak of the Divine establishment of the Tabernacle and the Temple (Exodus 40:1-5, 9-10, 34-35 and IIIKings 8:1, 3-4, 6-7, 9, 10-11). The third reading, taken from the Prophecy to Prophet Ezekiel ( Ezekiel 43:27-44:4) speaks of the Theotokos as the living Temple of God.

During the Divine Liturgy, in the reading of the Epistle of Saint Paul to the Hebrews (9:1-7), we are taught that all things which were done in the Temple of the Old Testament were a Prophecy of what would be fulfilled by our Saviour. In the Gospel of Saint Luke (10:38-42, 11:27-28), which is read at every Feast of the Mother of God, we hear: Blessed is the womb that bare thee, and the paps which thou hast sucked. We are reminded to glorify our Lord and bless His mother, who brought us our salvation.

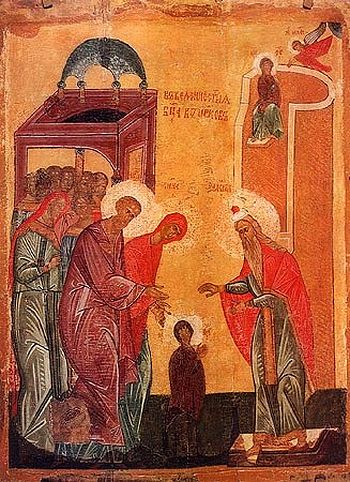

Icon of the Feast

The Orthodox teaching on the The Entry of the Theotokos into the Temple as the heralding of the salvation of mankind is seen in the Icon of the Feast. The central theme of the icon is the Holy of Holies (1) in the Temple which is about to receive a blessing far superior to any of its former blessings. The priest Zacharias, the father of St. John the Baptist, receives Panagia at the gates of the Temple (3) and in this way prophesies that the Virgin Mary is the New Ark of the Covenant. Saints Joachim and Anna (4), accompanied by virgins of Jerusalem, carrying torches in procession, bring Panagia as a well-pleasing sacrifice. The Theotokos is brought to the gates and ascends to the Holy of Holies where she is cared for by angels (2). Notice that the young virgins do not have their heads covered but that the Theotokos has her head covered. Also the garments of the Mother of God resemble those of Saint Anna and not of the young virgins. The Theotokos, although a child, is already a perfected woman that has reached full spiritual maturity. She who in body is but three years old, and yet in the spirit is full of years (Ode three of the Second Canon).